Who the Heck was Kilroy???

In 1946, the American Transit Association through its radio

program, “Speak America,” sponsored a nationwide contest to find the REAL

Kilroy, offering a prize of a real trolley car to the person who could prove

himself to be the genuine article.

Almost 40 men stepped forward to make that claim, but only James Kilroy from Halifax, Massachusetts had evidence of his identity. Kilroy was a 46-year old shipyard worker during the war. He worked as a checker at the Fore River Shipyard in Quincy. His job was to go around and check on the number of rivets completed. Riveters were on piecework and got paid by the rivet. Kilroy would count a block of rivets and put a check mark in semi-waxed lumber chalk, so the rivets wouldn’t be counted twice. When Kilroy went off duty, the riveters would erase the marks. Later on. An off-shift inspector would come through and count the rivets a second time, resulting in double pay for the riveters.

One day Kilroy's boss called him into his office. The foreman was upset about all the wages being paid to riveters, and asked him to investigate. It was then that he realized what had been going on. The tight spaces he had to crawl in to check the rivets didn't lend themselves to lugging around a paint can and brush, so Kilroy decided to stick with the waxy chalk.

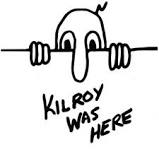

He continued to put his checkmark on each job he inspected, but added "KILROY WAS HERE" in king-sized letters next to the check, and eventually added the sketch of the chap with the long nose peering over the fence, and that became part of the Kilroy message. Once he did that, the riveters stopped trying to wipe away his marks.

Ordinarily the rivets and chalk marks would have been covered up with paint. With war on, however, ships were leaving the Quincy Yard so fast that there wasn't time to paint them. As a result, Kilroy's inspection "trademark" was seen by thousands of servicemen who boarded the troopships the yard produced.

His message apparently rang a bell with the servicemen, because they picked it up and spread it all over Europe and the South Pacific. Before the war's end, "Kilroy" had been here, there, and everywhere on the long haul to Berlin and Tokyo.

To the unfortunate troops outbound in those ships, however, he was a complete mystery; all they knew for sure was that some jerk named Kilroy had "been there first." As a joke, U.S. servicemen began placing the graffiti wherever they landed, claiming it was already there when they arrived. Kilroy became the U.S. super-GI who had always "already been" wherever GI's went. It became a challenge to place the logo in the most unlikely places imaginable (it is said to be atop Mt. Everest, the Statue of Liberty, the underside of the Arc De Triomphe, and even scrawled in the dust on the moon.)

And as the war went on, the legend grew. Underwater demolition teams routinely sneaked ashore on Japanese-held islands in the Pacific to map the terrain for the coming invasions by U.S. troops (and thus, presumably, were the first GI's there). On one occasion, however, they reported seeing enemy troops painting over the Kilroy logo!

In 1945, an outhouse was built for the exclusive use of Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill at the Potsdam conference. The first person inside was Stalin, who emerged and asked his aide (in Russian), "Who is Kilroy?"

To help prove his authenticity in 1946, James Kilroy brought along officials from the shipyard and some of the riveters. He won the trolley car, which he gave to his nine children as a Christmas gift and set it up as a playhouse in the Kilroy front yard in Halifax, Massachusetts.

So Now You Know!

Almost 40 men stepped forward to make that claim, but only James Kilroy from Halifax, Massachusetts had evidence of his identity. Kilroy was a 46-year old shipyard worker during the war. He worked as a checker at the Fore River Shipyard in Quincy. His job was to go around and check on the number of rivets completed. Riveters were on piecework and got paid by the rivet. Kilroy would count a block of rivets and put a check mark in semi-waxed lumber chalk, so the rivets wouldn’t be counted twice. When Kilroy went off duty, the riveters would erase the marks. Later on. An off-shift inspector would come through and count the rivets a second time, resulting in double pay for the riveters.

One day Kilroy's boss called him into his office. The foreman was upset about all the wages being paid to riveters, and asked him to investigate. It was then that he realized what had been going on. The tight spaces he had to crawl in to check the rivets didn't lend themselves to lugging around a paint can and brush, so Kilroy decided to stick with the waxy chalk.

He continued to put his checkmark on each job he inspected, but added "KILROY WAS HERE" in king-sized letters next to the check, and eventually added the sketch of the chap with the long nose peering over the fence, and that became part of the Kilroy message. Once he did that, the riveters stopped trying to wipe away his marks.

Ordinarily the rivets and chalk marks would have been covered up with paint. With war on, however, ships were leaving the Quincy Yard so fast that there wasn't time to paint them. As a result, Kilroy's inspection "trademark" was seen by thousands of servicemen who boarded the troopships the yard produced.

His message apparently rang a bell with the servicemen, because they picked it up and spread it all over Europe and the South Pacific. Before the war's end, "Kilroy" had been here, there, and everywhere on the long haul to Berlin and Tokyo.

To the unfortunate troops outbound in those ships, however, he was a complete mystery; all they knew for sure was that some jerk named Kilroy had "been there first." As a joke, U.S. servicemen began placing the graffiti wherever they landed, claiming it was already there when they arrived. Kilroy became the U.S. super-GI who had always "already been" wherever GI's went. It became a challenge to place the logo in the most unlikely places imaginable (it is said to be atop Mt. Everest, the Statue of Liberty, the underside of the Arc De Triomphe, and even scrawled in the dust on the moon.)

And as the war went on, the legend grew. Underwater demolition teams routinely sneaked ashore on Japanese-held islands in the Pacific to map the terrain for the coming invasions by U.S. troops (and thus, presumably, were the first GI's there). On one occasion, however, they reported seeing enemy troops painting over the Kilroy logo!

In 1945, an outhouse was built for the exclusive use of Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill at the Potsdam conference. The first person inside was Stalin, who emerged and asked his aide (in Russian), "Who is Kilroy?"

To help prove his authenticity in 1946, James Kilroy brought along officials from the shipyard and some of the riveters. He won the trolley car, which he gave to his nine children as a Christmas gift and set it up as a playhouse in the Kilroy front yard in Halifax, Massachusetts.

So Now You Know!

Monopoly - I did not

know this!

(You'll never look at the game the same way again!)

Starting in 1941, an increasing number of British Airmen found themselves as the involuntary guests of the Third Reich, and the Crown was casting about for ways and means to facilitate their escape...

Now obviously, one of the most helpful aids to that end is a useful and accurate map, one showing

not only where stuff was, but also showing the locations of 'safe houses' where a POW on-the-lam could go for food and shelter.

Paper maps had some real drawbacks -- they make a lot of noise when you open and fold them, they wear out rapidly, and if they get wet, they turn into mush.

Someone in MI-5 (similar to America 's OSS ) got the idea of printing escape maps on silk. It's durable, can be scrunched-up into tiny wads, and unfolded as many times as needed, and makes no noise whatsoever.

At that time, there was only one manufacturer in Great Britain that had perfected the technology of printing on silk, and that was John Waddington, Ltd. When approached by the government, the firm was only too happy to do its bit for the war effort.

By pure coincidence, Waddington was also the U.K. Licensee for the popular American board game, Monopoly. As it happened, 'games and pastimes' was a category of item qualified for insertion into 'CARE packages', dispatched by the International Red Cross to prisoners of war.

Under the strictest of secrecy, in a securely guarded and inaccessible old workshop on the grounds of Waddington's, a group of sworn-to-secrecy employees began mass-producing escape maps, keyed to each region of Germany or Italy where Allied POW camps were regional system). When processed, these maps could be folded into such tiny dots that they would actually fit inside a Monopoly playing piece.

As long as they were at it, the clever workmen at Waddington's also managed to add:

1. A playing token, containing a small magnetic compass

2. A two-part metal file that could easily be screwed together

3. Useful amounts of genuine high-denomination German, Italian, and French currency, hidden within the piles of Monopoly money!

British and American air crews were advised, before taking off on their first mission, how to identify a 'rigged' Monopoly set -- by means of a tiny red dot, one cleverly rigged to look like an ordinary printing glitch, located in the corner of the Free Parking square.

Of the estimated 35,000 Allied POWS who successfully escaped, an estimated one-third were aided in their flight by the rigged Monopoly sets.. Everyone who did so was sworn to secrecy indefinitely, since the British Government might want to use this highly successful ruse in still another, future war.

The story wasn't declassified until 2007, when the surviving craftsmen from Waddington's, as well as the firm itself, were finally honored in a public ceremony.

It's always nice when you can play that 'Get Out of Jail' Free' card!

I realize many of you are (probably) too young to have any personal connection to WWII (Dec. '41 to Aug. '45), but this is still interesting.

Story verification:

http://blogs.wsj.com/informedreader/2007/11/19/wwii-pows-perk-monopoly-with-real-money/

(You'll never look at the game the same way again!)

Starting in 1941, an increasing number of British Airmen found themselves as the involuntary guests of the Third Reich, and the Crown was casting about for ways and means to facilitate their escape...

Now obviously, one of the most helpful aids to that end is a useful and accurate map, one showing

not only where stuff was, but also showing the locations of 'safe houses' where a POW on-the-lam could go for food and shelter.

Paper maps had some real drawbacks -- they make a lot of noise when you open and fold them, they wear out rapidly, and if they get wet, they turn into mush.

Someone in MI-5 (similar to America 's OSS ) got the idea of printing escape maps on silk. It's durable, can be scrunched-up into tiny wads, and unfolded as many times as needed, and makes no noise whatsoever.

At that time, there was only one manufacturer in Great Britain that had perfected the technology of printing on silk, and that was John Waddington, Ltd. When approached by the government, the firm was only too happy to do its bit for the war effort.

By pure coincidence, Waddington was also the U.K. Licensee for the popular American board game, Monopoly. As it happened, 'games and pastimes' was a category of item qualified for insertion into 'CARE packages', dispatched by the International Red Cross to prisoners of war.

Under the strictest of secrecy, in a securely guarded and inaccessible old workshop on the grounds of Waddington's, a group of sworn-to-secrecy employees began mass-producing escape maps, keyed to each region of Germany or Italy where Allied POW camps were regional system). When processed, these maps could be folded into such tiny dots that they would actually fit inside a Monopoly playing piece.

As long as they were at it, the clever workmen at Waddington's also managed to add:

1. A playing token, containing a small magnetic compass

2. A two-part metal file that could easily be screwed together

3. Useful amounts of genuine high-denomination German, Italian, and French currency, hidden within the piles of Monopoly money!

British and American air crews were advised, before taking off on their first mission, how to identify a 'rigged' Monopoly set -- by means of a tiny red dot, one cleverly rigged to look like an ordinary printing glitch, located in the corner of the Free Parking square.

Of the estimated 35,000 Allied POWS who successfully escaped, an estimated one-third were aided in their flight by the rigged Monopoly sets.. Everyone who did so was sworn to secrecy indefinitely, since the British Government might want to use this highly successful ruse in still another, future war.

The story wasn't declassified until 2007, when the surviving craftsmen from Waddington's, as well as the firm itself, were finally honored in a public ceremony.

It's always nice when you can play that 'Get Out of Jail' Free' card!

I realize many of you are (probably) too young to have any personal connection to WWII (Dec. '41 to Aug. '45), but this is still interesting.

Story verification:

http://blogs.wsj.com/informedreader/2007/11/19/wwii-pows-perk-monopoly-with-real-money/

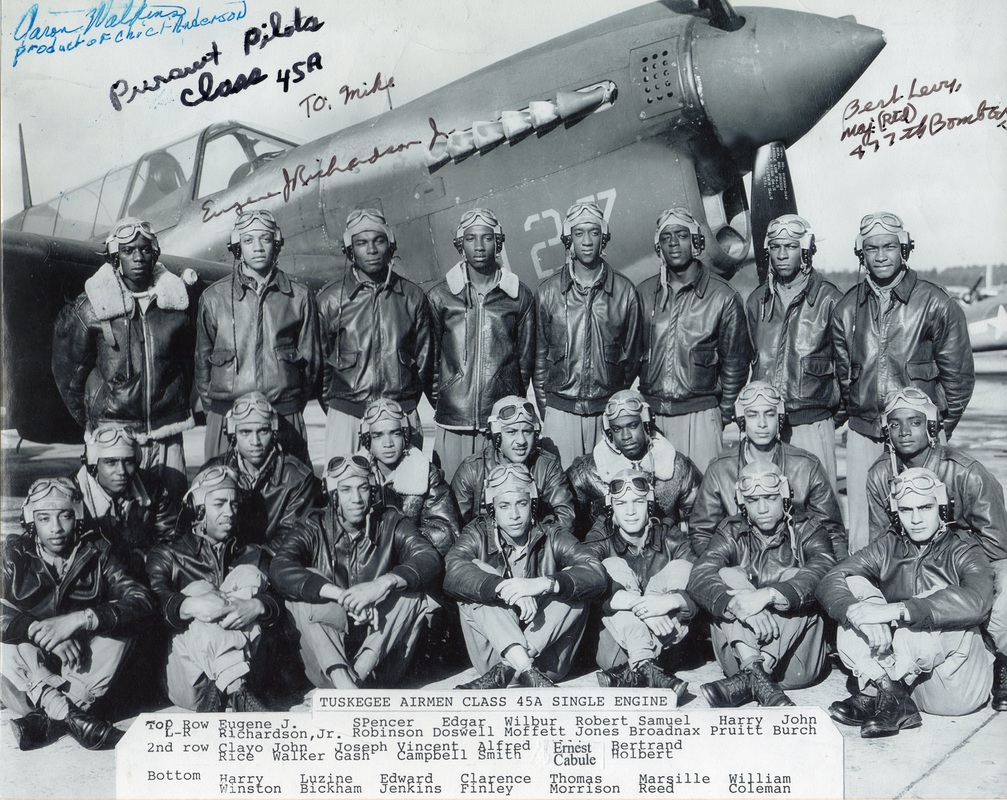

The Tuskegee Airmen

The Tuskegee Airmen were dedicated, determined young men who enlisted to become America's first black military airmen, at a time when there were many people who thought that black men lacked intelligence, skill, courage and patriotism.

The black airmen who became single-engine or multi-engine pilots were trained at Tuskegee Army Air Field (TAAF) in Tuskegee, Alabama. Many of the 450 pilots who were trained at TAAF served overseas in the 99th Pursuit Squadron. They were later joined by the 100th, 301st and the 302nd African-American fighter squadrons. Together these squadrons formed the 332nd fighter group. Among other operations, the airmen successfully escorted numerous bomber missions over Sicily, the Mediterranean and North Africa. Bomber crews named the Tuskegee Airmen "Red-Tail Angels" after the red tail markings on their aircraft. The German Luftwaffe called them "Black Bird Men."

The outstanding record of black airmen in World War II was accomplished by men whose names will forever live in hallowed memory. Each one accepted the challenge, proudly displayed his skill and determination while suppressing internal anger from humiliation and indignation caused by a segregated military and frequent experiences of racism and bigotry, at home and overseas.

The Tuskegee Airmen were awarded numerous high honors, including Distinguished Flying Crosses, Legions of Merit, Silver Stars, Purple Hearts, and the Croix de Guerre. A distinguished Unit Citation was awarded to the 332nd Fighter Group for "outstanding performance and extraordinary heroism" in 1945.

The black airmen who became single-engine or multi-engine pilots were trained at Tuskegee Army Air Field (TAAF) in Tuskegee, Alabama. Many of the 450 pilots who were trained at TAAF served overseas in the 99th Pursuit Squadron. They were later joined by the 100th, 301st and the 302nd African-American fighter squadrons. Together these squadrons formed the 332nd fighter group. Among other operations, the airmen successfully escorted numerous bomber missions over Sicily, the Mediterranean and North Africa. Bomber crews named the Tuskegee Airmen "Red-Tail Angels" after the red tail markings on their aircraft. The German Luftwaffe called them "Black Bird Men."

The outstanding record of black airmen in World War II was accomplished by men whose names will forever live in hallowed memory. Each one accepted the challenge, proudly displayed his skill and determination while suppressing internal anger from humiliation and indignation caused by a segregated military and frequent experiences of racism and bigotry, at home and overseas.

The Tuskegee Airmen were awarded numerous high honors, including Distinguished Flying Crosses, Legions of Merit, Silver Stars, Purple Hearts, and the Croix de Guerre. A distinguished Unit Citation was awarded to the 332nd Fighter Group for "outstanding performance and extraordinary heroism" in 1945.

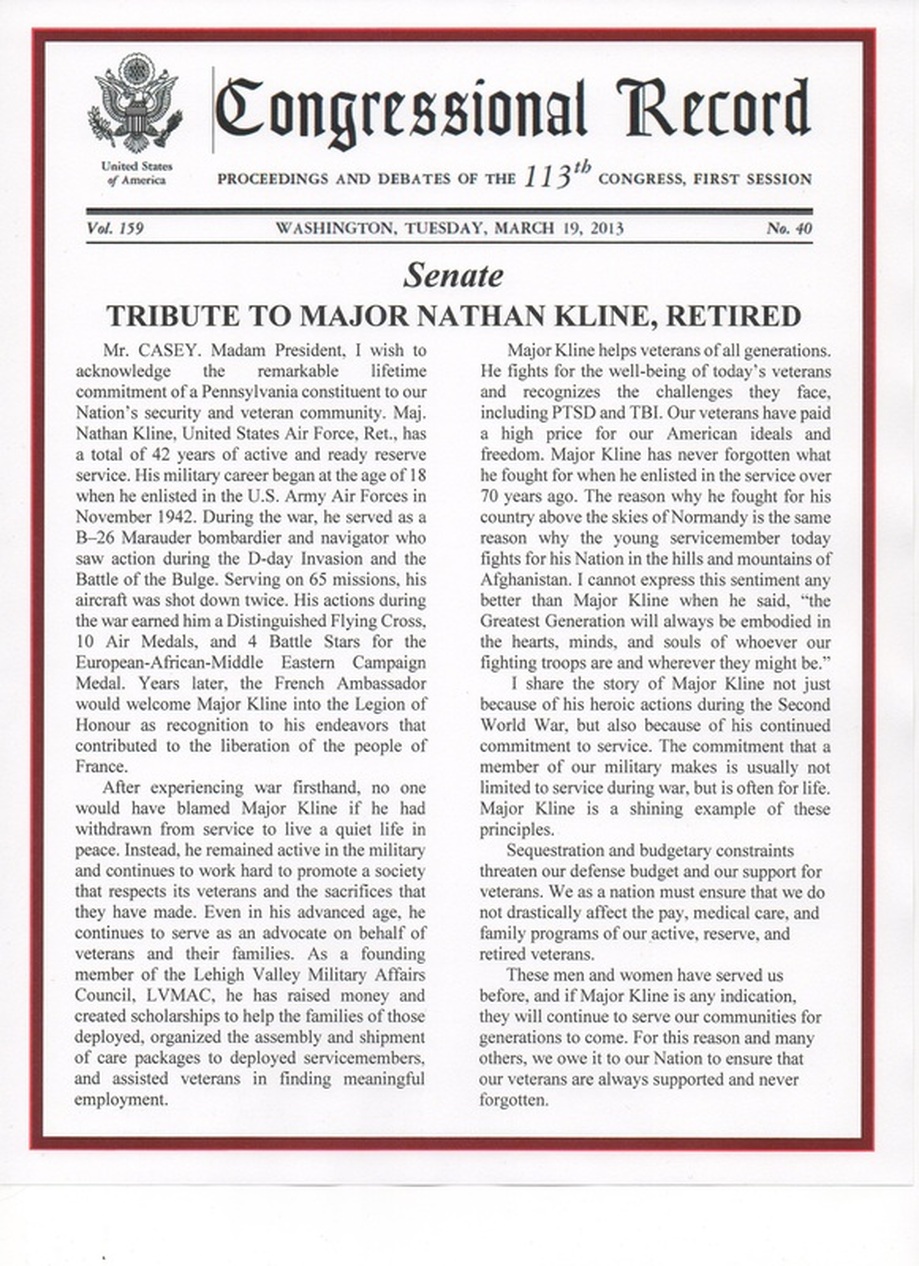

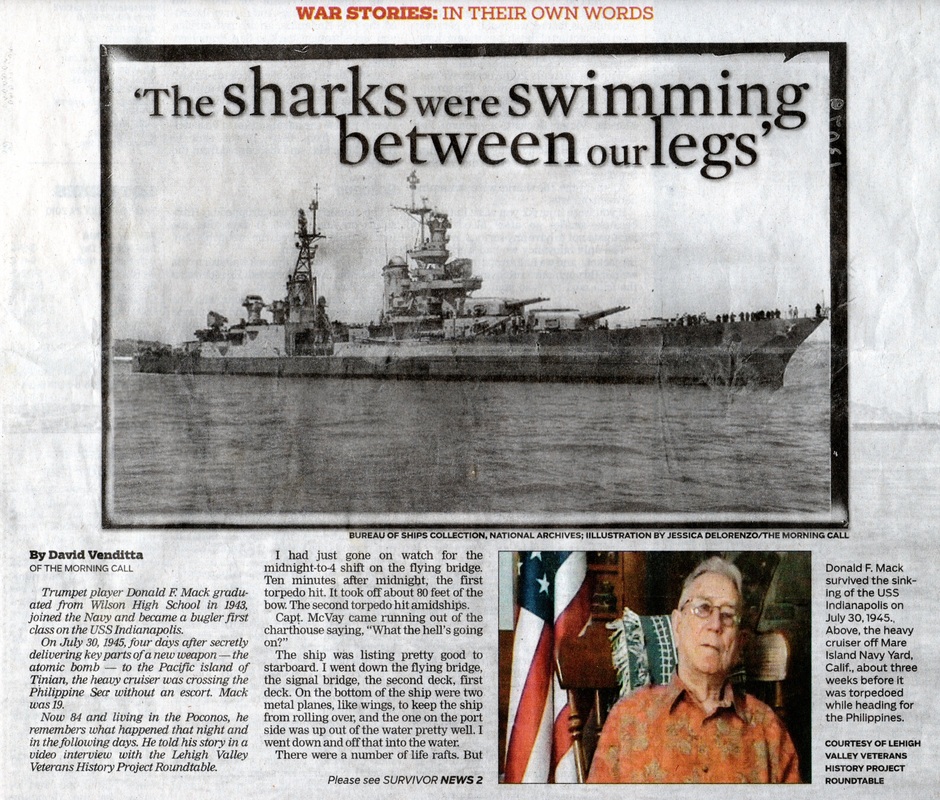

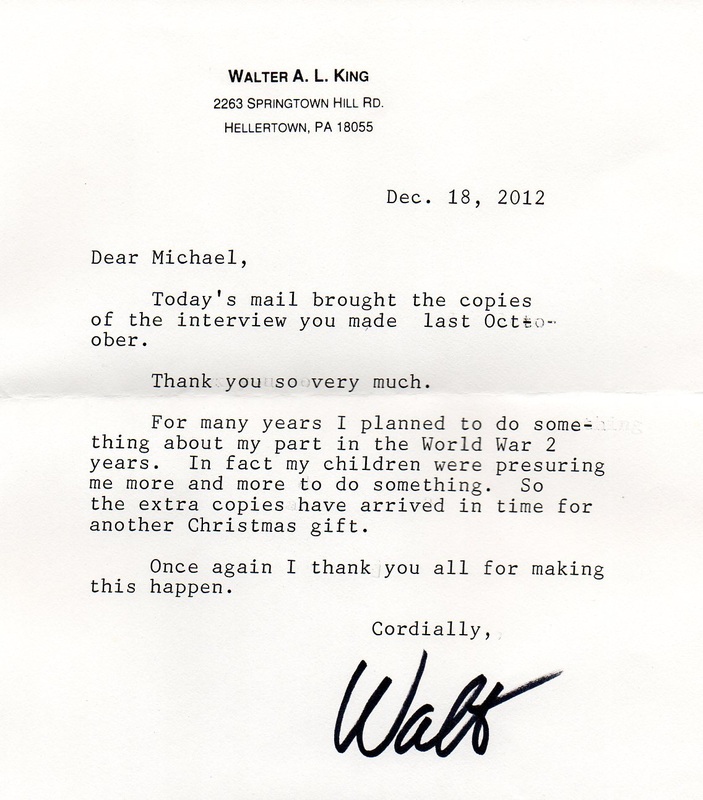

War Stories: In Their Own Words

Pennsylvania Veterans Tell

of Sacrifice and Courage

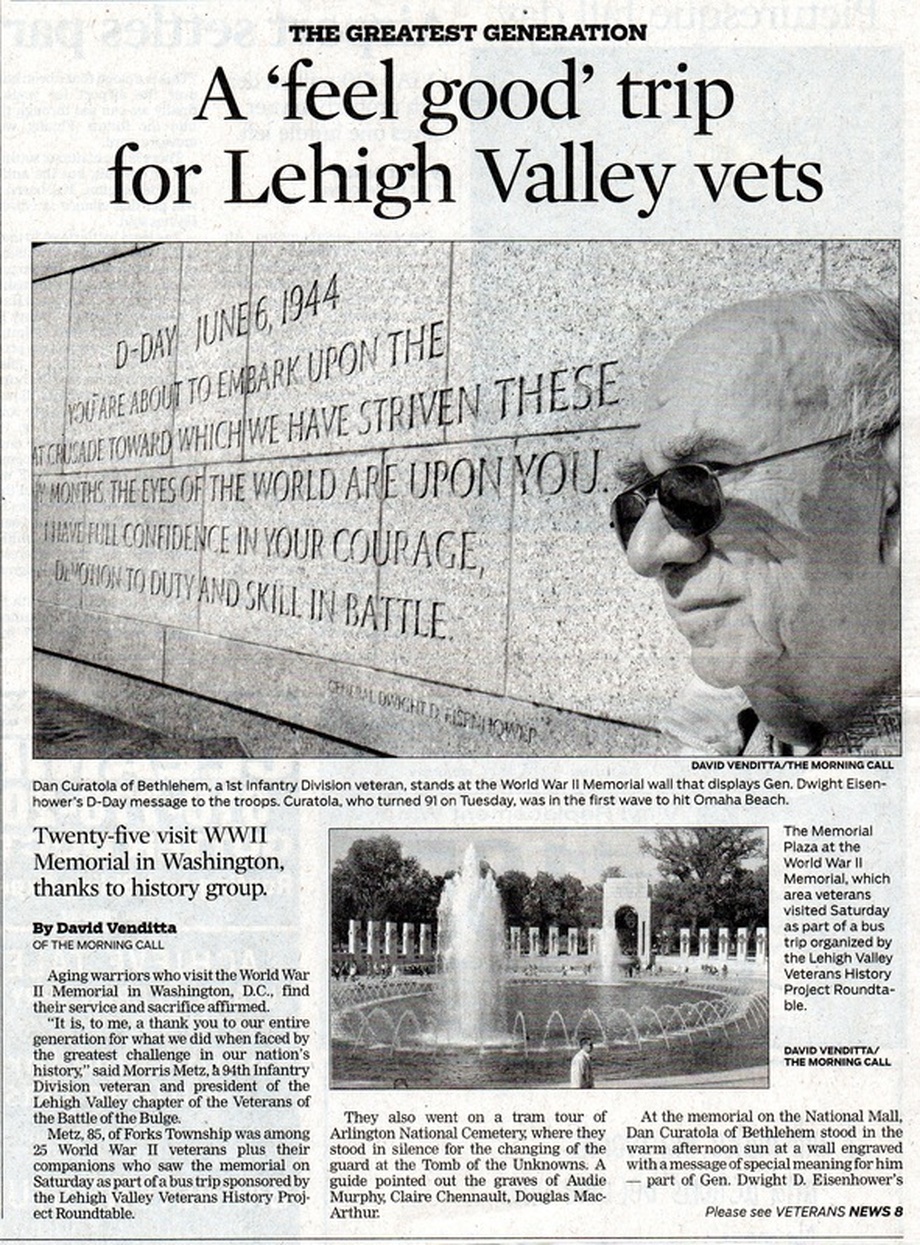

By David Venditta

An original 176-page collection of stories as told by Pennsylvanians who served in the armed forces during the major U.S. wars of the 20th century.

War Stories: In Their Own Words is a collection of stories as told by Pennsylvanians who served in the armed forces during the major U.S. wars of the 20th century - World Wars I and II, the Cold War, and the Korean and Vietnam wars. Published in The Morning Call over the last 12 years, these are vivid, personal accounts of men and women from the Lehigh Valley and beyond who had a role on the world stage at critical times. They are stories of heartbreak and suffering, humanity and courage that take us from the earliest days of the 1900s, when the cavalry was chasing Pancho Villa into the Mexican desert, to the early 1970s, when GIs slogged through the rice paddies of Vietnam

For more than a decade, author David Venditta has documented the personal stories of America's wars by letting the veterans speak for themselves. His in-depth interviews of men and women who served in combat zones are a remarkable record of courage and survival. This volume for the first time brings together a wide-ranging selection of the stories, presented with photos, maps and notes on the veterans' post-war years. David is an editor at The Morning Call in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

Click here to order your copy today or call 610-508-1517.

By David Venditta

An original 176-page collection of stories as told by Pennsylvanians who served in the armed forces during the major U.S. wars of the 20th century.

War Stories: In Their Own Words is a collection of stories as told by Pennsylvanians who served in the armed forces during the major U.S. wars of the 20th century - World Wars I and II, the Cold War, and the Korean and Vietnam wars. Published in The Morning Call over the last 12 years, these are vivid, personal accounts of men and women from the Lehigh Valley and beyond who had a role on the world stage at critical times. They are stories of heartbreak and suffering, humanity and courage that take us from the earliest days of the 1900s, when the cavalry was chasing Pancho Villa into the Mexican desert, to the early 1970s, when GIs slogged through the rice paddies of Vietnam

For more than a decade, author David Venditta has documented the personal stories of America's wars by letting the veterans speak for themselves. His in-depth interviews of men and women who served in combat zones are a remarkable record of courage and survival. This volume for the first time brings together a wide-ranging selection of the stories, presented with photos, maps and notes on the veterans' post-war years. David is an editor at The Morning Call in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

Click here to order your copy today or call 610-508-1517.